MU SOCHUA – CAMBODIA

“You try until the very end, and if there is no very end, you continue.”

How would you describe the living conditions in Cambodia today? Especially since Covid-19, the situation has become very difficult. Hun Sen [Prime Minister of Cambodia since 19821, editor’s note] totally locked the whole city [of Phnom Pen] down without giving people food. Hundreds of people, who went onto social media to complain and to protest, were either arrested or reeducated for spreading “fake news”. But actually they were hungry, scared, having to pay electricity bill, having to pay the debt, not knowing what to feed their children the next day and this is 2021! Their stomachs are still empty. They are struggling hard, and their rights are violated.

What was it like being a liberal politician in Cambodia and has it become easier over time to call yourself liberal? When I was minister and a Member of Parliament, to declare yourself a liberal in Cambodia, you constantly have to defend your position. I was often asked “Do you support LGBT? Why?”. I was fighting against gender based violence, domestic violence, even addressed taboo topics like marital rape. That is very liberal but you have to say, it is about human rights. Think of it as if this person is your wife, your child, your own daughter, living under the same roof. She is your family and you defend her rights. It is a duty, a responsibility and it is in the law. Today, I still have to explain why I defend some causes. For example, just recently, there was the case of a woman, who nearly got raped in a car but could escape. She is a TV presenter in Cambodia. It became a really big story because the guy involved is a tycoon from the ruling party. I talked about it on Facebook. But then I saw comments such as: “She is just trash. Everybody who is in the entertainment sector is trash.” How can they say that? She is not just worth defending. She is your responsibility, our responsibility to defend.

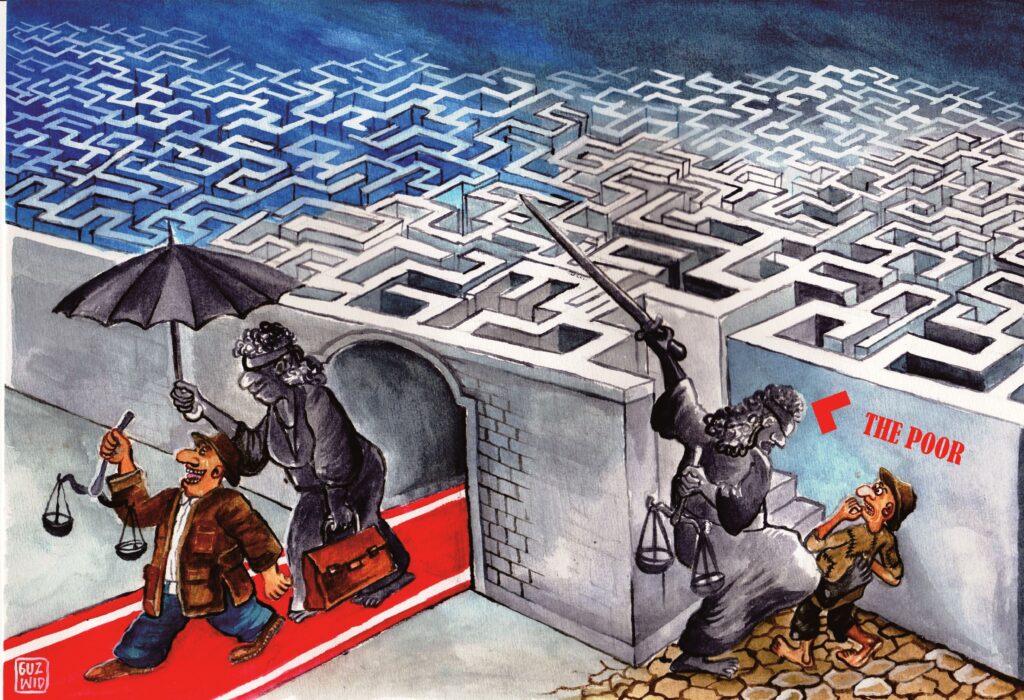

By Guzwid for this year’s HUMAN RIGHTS IN ASEAN - The Cartoonists Perspective Exhibition

How important is freedom of speech for the promotion of freedom and democracy? Once you have access to information, your mind starts working - you start to think critically and you want people to be thinking critically for their own lives and for the lives of humanity. For me, it is very important to have the right information and information from different sources, as well as information to generate critical thinking. It is true that when you liberate your mind, you take away the shackles that keeps you as a prisoner. To me, that full range of freedom is so important.

What role does it play in your work and human rights activism that you are a woman? It is a big part of it. As women, we share the struggles that we have to overcome. Sometimes it is morally challenging, for example when defending a sex worker. But who is going to defend her, if it’s not you as a woman sharing the same flesh? When stepping up for other women, I have learned to balance out the emotion with reality and with the tool that you can use in order achieve what you want: the law. Being outraged is not going to help win cases. It is through the law but even with the law, you can still lose. It is through strategy, advocacy, networking, finding allies.

What are the personal consequences of your activism? I am in exile as a consequence of being outspoken, of defending, believing in freedom, in justice, in human rights and in dignity. Another consequence is that you are labelled. You cannot describe this label in one word – it makes people judge you for what you are doing, not for who you are. They can judge you by respecting you or they can judge you by saying that she is a trouble maker.

Just recently, there has been a verdict against you in Cambodia. What happened? They sentenced me to 20 years in prison. I never had the right to return home to defend myself in court, although I have tried. They took away my passport. The Cambodian embassy in Washington, DC did not even let us apply for a visa. They put out a statement justifying themselves by declaring us as “terrorists”. If we are terrorists, they should have taken us home to Cambodia and put us on trial. They could have even asked the US authority to arrest this “terrorist” - and I would have been happy to be arrested. At least I could go home, to defend our rights. That is the point about defending human rights and the burden of being a human rights defender. You cannot afford to say to yourself: “I give up”. You try until the very end, and if there is no very end, you continue.

You receive a lot of online hate on Social Media. Which of your statements are causing hate speech and what kind of hate speech do you have to endure? I go live on Facebook nearly every day and sometimes I have as many as half a million viewer. There are three types of comments. Those who are in favor, of course. Not just members of my party but those who are pro-democracy. Then there are those who are in the middle and thirdly those who support the ruling Cambodia’s People Party (CPP). One of the worst comments I got was someone saying they want to put something inside of me and let it explode - inside, meaning your vagina! I get sexualized comments all the time on Facebook. How can you take comments like this? My daughter always says: “Ma, just don’t read it!” But it is just there.

What does it do to you? In the beginning of the day, when I open everything, I do not look at comments because sometimes, one little thing triggers a lot of feelings. Often, I knit when I have a conversation or debate democracy with our team in Cambodia and with Sam Rainsy [former leader of the opposition in Cambodia, now also in exile, editor’s note], who also receives a lot of violent hate speech and threats. I knit big sweaters for all my family members but none of them are perfect. The last one I knitted for granddaughter, the stitches were totally wrong but I don’t undo them because it is a part of history, for fighting for rights and democracy. I say to them: “See, this is when we were fighting for this and this is when I was watching and listening to a fighting woman who was crying the heart out for the pain that she suffers”.

As a human rights defender outside of Cambodia, you are the eyes and ears for the international community to tell them about what is happening in your home country. Is that how you perceive yourself? I try to not only focus on Cambodia and to be more open to other human rights issues and democracy in other parts of the world. Human rights issues are global issues that you have to put in context. But I also work in other fields. Right now, I live in the US and we have a Cambodian community here as well. Just recently, they released the census which shows that only 16 percent of Cambodians in the US finished college. And we have the highest number of welfare recipients. So I am talking to my community now and say, this is not right. We are in America. This is the system. We are part of the system. We pay taxes. We have to be engaged. We have to run for offices.

SHORT BIOGRAPHY

Mu Sochua is a Cambodian politician and human rights activist. Asked whether she would define herself more as a human rights defender or as a politician she responds: “It is neither nor, it is both. And with the qualified adjectives liberal and democrat”.